If you or someone you love has experienced an overwhelming life event, you may be left wondering: how does this trauma affect the brain?When we go through...

If you or someone you love has experienced an overwhelming life event, you may be left wondering: how does this trauma affect the brain?

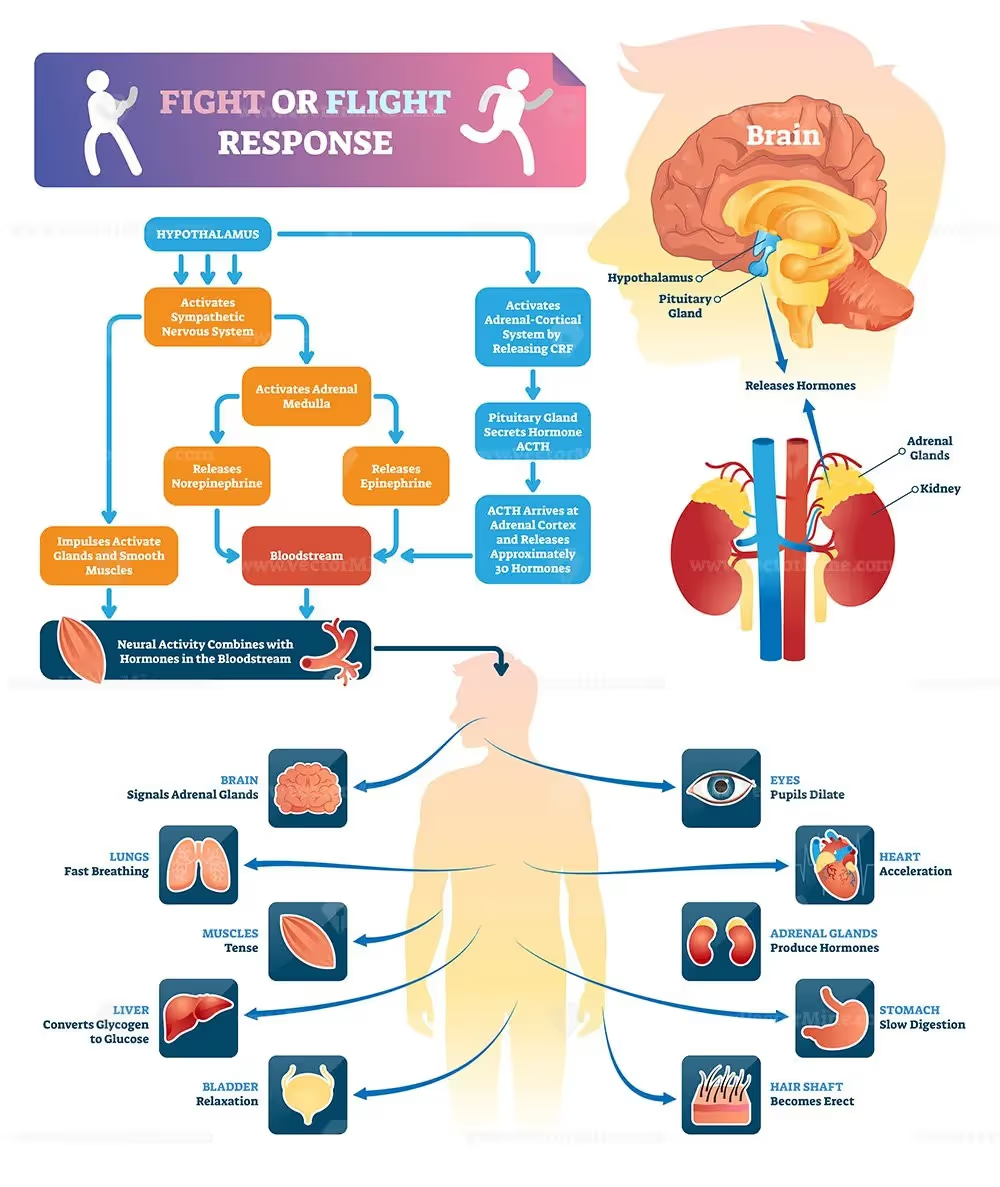

When we go through situations that leave us feeling unsafe and powerless, the brain will try to send signals to help us reestablish security, typically through the "flight or fight" response.

However, when such reactions fail, there may be longer-term changes in specific regions of the brain--specifically the amygdala, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex, and dysregulated norepinephrine and cortisol levels.

Traumatic events are not black-and-white.

There are many forms of trauma at varying degrees of intensity and long-term impact.

However, there are specific instances that are commonly recognized to be traumatic.

This includes: various forms of abuse and violence such as sexual, domestic, mental/verbal, emotional, and religious; witnessing a violent crime or event; war and terrorism; bodily incapacitation such as losing a limb or becoming paralyzed; being kidnapped or taken hostage.

Some counselors also recognize the traumatic impacts of more common events such as betrayal/infidelity, car accidents, and sudden losses.

Before addressing the specific ways trauma affects the brain, it is important to review the body's "stress response."

The body's nervous system can be divided into the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS).

The PNS is divided further into the autonomic (ANS) and somatic nervous systems. The ANS includes the sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric nervous systems which interact with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to regulate stress and physiological responses.

This interaction between the CNS, ANS, and HPA is what helps the body maintain homeostasis and adapt to its environment.

They do this through the chemical/hormonal mediators norepinephrine (noradrenaline), epinephrine (adrenaline), and cortisol.

When our brain's perceive a stressor, the CNS signals to the sympathetic nervous system to release norepinephrine and epinephrine into the bloodstream.

These chemicals attach to receptors in bodily tissues and trigger physiological responses intended to aid survival--i.e., to either fight or flee.

Such responses include increased blood pressure and heart rate, dilation of lung bronchi to increase oxygen output, and dilation of pupils.

Finally, after the initial activation of the stress response, the HPA releases cortisol into the bloodstream which triggers the release of stored glucose, fats, and amino acids to be used in sustaining the heightened physiological state.

Ultimately, all these reactions are geared towards survival, and once the threat is dealt with or escaped, the parasympathetic nervous system releases further chemical transmitters to bring the body back into equilibrium.

However, trauma is a unique type of stressor that may result in the PNS not being able to bring about normal homeostasis.

Traumatic events are unique stressors in that they are extreme, cumulative, and/or prolonged. Unlike short-term stressors such as, say, an upcoming exam or speaking in public, the continual or extreme activation of the stress response alters brain "circuits" or neural pathways.

This is particularly true when the trauma occurs in childhood, as the developing mind is highly elastic and susceptible to changes.

It is important to note that "trauma at different stages in life will presumably have different effects on brain development" (Bremner, 2006).

Studies done with animals showed that increased stress in infancy and youth, such as neglect or abuse, decreased cortisol receptors in the hippocampus, hypothalamus, and frontal cortex while increasing the levels of fluid activating the body's "stress response."

This means that trauma increases the brain's rate of reacting to stressors while decreasing its ability to eliminate the threat and/or calm down.

Cortisol plays a critical role not only in reacting to threats, but signaling to the body that the threat has been dealt with and it is okay to calm down.

This hyper-elevation of cortisol during traumatic experiences leads to lower levels in the future, while the brain is also becoming more sensitive to perceived threats and releasing norepinephrine/epinephrine.

Many trauma survivors develop Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

PTSD manifests in specific symptoms, "including intrusive thoughts, hyperarousal, flashbacks, nightmares, and sleep disturbances, changes in memory and concentration, and startle responses" (Bremner 2006).

Perhaps one of the most well-known symptoms of PTSD is memory alterations.

Victims often experience flashbacks that feel as if they are happening in the present moment, triggering the stress response to a non-existent threat.

According to various studies, it is unclear how the dysfunction with verbal declarative memory is related to trauma, for it seems to vary between single-event trauma and repeated trauma, as well as environmental factors and genetic predispositions.

The brain is a complex organ, constantly adapting to internal and external factors.

The body has a highly regulated "stress response" which activates upon perceiving a stressor, signaling the release of chemicals/neurotransmitters in preparation for fight or flight.

When we experience a traumatic event or series of events, the stress response can become dysregulated, with higher sensitivity to perceived threats, while having lower levels of cortisol to alleviate the stress.

Over time this can develop into PTSD or other cognitive disorders, further impacting memory and emotional regulation.

https://www.zrtlab.com/blog/archive/creating-balance-stress-response/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181836/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8625891/

During a trauma-informed therapy session, the therapist will prioritize creating a safe and supportive environment for you to share your experiences. They will listen empathetically, validate your feelings, and help you develop coping strategies to manage your symptoms. The therapist will also work collaboratively with you to create a personalized treatment plan that meets your unique needs and promotes healing and resilience.

Develop a self-soothing toolkit filled with comforting items or activities that can help calm and ground you during challenging moments. Utilize grounding and relaxation techniques to manage overwhelming emotions, and reach out to your support network for reassurance and encouragement.

Remember that taking care of yourself is essential for your overall well-being and progress in therapy.

Acknowledge any feelings of guilt and work with your therapist to challenge and reframe these beliefs, recognizing that self-care is a crucial component of the healing process.

If trauma is left unaddressed, it can lead to a host of problems. This can include mental health issues such as PTSD treatment, anxiety, and depression, as well as physical health issues due to the body's response to stress. Trauma can also affect one's ability to form healthy relationships and lead to social isolation. It's important to seek help after experiencing traumatic events to begin the healing process.

Yes, trauma-informed care principles can be applied in both individual and group therapy settings to create a supportive and compassionate environment for healing and growth.